Against Lake Powell: Why Our Favorite Reservoir Should be Drained

February 3, 2022

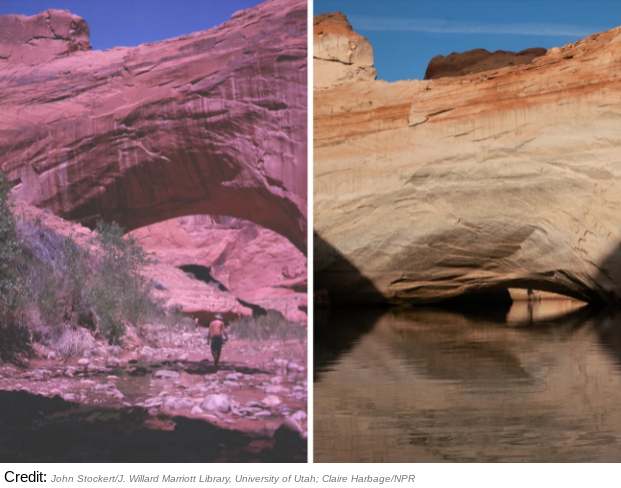

The graph of Lake Powell’s water level over the past year looks like a ski slope. Thirteen of fourteen ramps are unusable. Houseboats are sinking into mud. Chalky white bathtub rings marr the canyon walls, ghosts of the reservoir’s former scale. The water’s retreat heralds the end of a recreational attraction, but it is also revealing a habitat obscured for over sixty years. “A portion of earth’s original paradise”, as environmentalist and author Edward Abbey described Glen Canyon, is slowly appearing as the water level plummets.

Glen Canyon dam has been clogging the Colorado River for so long that most don’t remember what the landscape used to look like. My only access to Glen Canyon as it once was is through the imagination, helped along by Abbey’s descriptions in “The Monkey Wrench Gang”. Instead of a winding desert canyon with lizards and river-carved sandstone, we were given a supersized swimming pool filled with motor skis and ringed by marinas.

All is not lost though; canyons can recover from damming. Richard Ingebretsen at the Grand Canyon Trust writes “Travel to the upper stretches of Cataract Canyon where the river has washed out virtually all of the sediment, erased the bathtub ring, and restored 14 large rapids—all of which were once drowned under Lake Powell….One thing is certain: when the lake is gone, the Glen will restore.” Lake Powell never should have existed in the first place, and now is as good a time as any to drain the lake and get Glen Canyon back.

Lake Powell was created in 1963 to provide electricity to the growing Southwest, store water for Upper Basin states, and join Lake Mead in regulating the flow of the Colorado, according to Nathan Rott at NPR. The reservoir has been increasingly struggling to do so as a result of the two-decade-long megadrought, amplified by human-caused climate change, that has been ravinging the western US. Ironically, the very activity that Lake Powell was created to fuel is now killing it.

The Glen Canyon Institute and others have been advocating the draining of the lake for decades. Their solution is a policy named “Fill Lake Mead First,” which would allow Lake Mead to fill to capacity before storing any water in Lake Powell. This policy would save at least 300,000 acre feet of water per year, according to a peer-reviewed study by the Institute.

While more water evaporates from Lake Mead than Lake Powell due to its larger surface area, the latter is simply a bad environment in which to store water. Porous sandstone makes up the base of Lake Powell, which absorbs vast quantities of water every year. Mead, on the other hand, sits atop hard rock that keeps water from trickling underground. Kenyon College claims that “There are regions, including Baja California and the Gulf of California, which would greatly benefit from the restoration of river flow. Draining Lake Powell means more water for the Colorado River states and Mexico, especially Colorado and Utah.” In draining the reservoir we lose some recreation, but our farmers and our region gain much-needed water.

Opponents claim that draining Lake Powell would harm the transition away from fossil fuels by decreasing the supply of hydropower in the region, but that supply is falling anyways. Soon neither Powell nor Mead will have enough water to generate much electricity. Kenyon College reports that “Lake Mead’s Hoover Dam could control the Colorado River without Lake Powell and could produce more power if Lake Powell’s water were stored behind the Hoover Dam. This would save money, water, and wild habitat.” Transitioning to Lake Mead could, in the long term, produce hydropower that would not have been otherwise possible.

This proposal won’t solve every water problem in the West as Jack Schmidt, a watershed scientist at Utah State University, told NPR “[the water shortage] problem can only be solved by reducing consumptive use.” But Lake Powell isn’t helping us get more water. The decline of water levels is revealing natural beauty that will bring tourism dollars to the region, even Lake Powell Marinas is encouraging people to come see the natural features of Glen Canyon, according to Rott at NPR.

Lake Powell means a lot to us here in the Grand Valley. Many have fond memories of the reservoir, but it’s time to make new ones in America’s “lost national park.” Powell never should have existed in the first place, and its existence has deprived us of one of the West’s most beautiful natural canyons. I want Glen Canyon back; I want Lake Powell gone. It’s time to rectify our past wrongs and keep our lands natural and healthy.